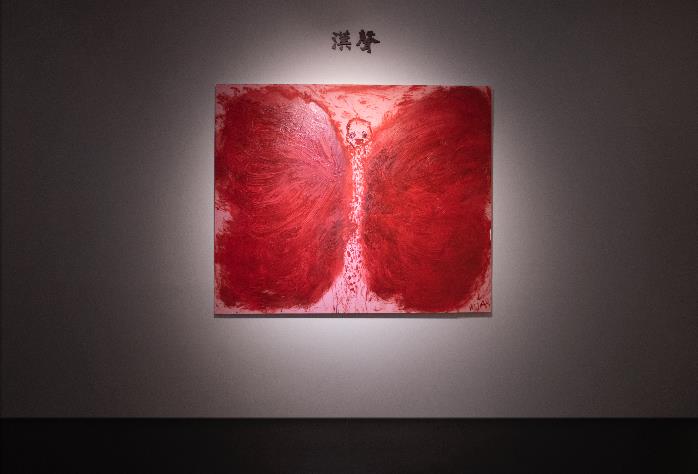

Leap of the Savage Beast

By Yang Jian

One Lao is our legend in this mundane era. He has finally arrived. Mount Song stands bare and exposed, and so does he. A naked and resolute aura of valor ripples through every place he sees and steps on. A long-neglected door of the soul, tarnished by time, is kicked open by this bearded, big-eyed rascal.

He came, and he was the Earth Fire that Lu Xun spoke of, stirring up the stagnant water with sheer force, going against everything that seemed right, and warning hypocrisy with the demeanor of a wild beast. His heart was keen, his hands were keen, and his pen was ke en; he was a man of keenness.

This rebellious spirit, with his teeth set in determination, in a world that was increasingly like a graveyard of technology and magic, was a guardian beast guarding something. What was it guarding? Simple: eternal, unending sincerity. It was so in the past, is so now, and will be so in the future. This was its vow, a spell inscribed on the painting.

For the frail and delicate, for the lifeless and artificial, he is the robust and vibrant, the one who dares to confront. Under the moon like snow, with stars filling the sky, the most desolate moment has arrived, when it is the spirit that must open new f rontiers, arrange new paths, and lead the way to survival.

He comes from the Wei-Jin era, from the Han and Tang dynasties, from the Five Dynasties. He is a fiery drink downed in one gulp, a character straight out of Water Margin or the Book of Masters, emerging from Han-era paintings, breaking out from the Classic of Mountains and Seas, every day a feast of innocence and joy, the moon always bright, each piece a work that reveals the true essence, each a transformation and refinement through the trials of life, each a work that reveals the core, like Han Shan’s poe ms that reveal the core, each a final piece, each stroke a final gamble, like a last will and testament.

At the towering peak stands the behemoth of the era, the weed of the battle still clashing. Fighting against the tide, Naked and unashamed, there is the frustration of. In the age of great false hood, he stands alone with sincerity. creating true art in false art, with both archetypal significance and event value. Two beasts, both beasts, He is also a beast. Looking at the beast at the peak, he bursts into a fit of guffaw.

In the era of the Classic of Mountains and Seas, the immortal beasts came to this age to suffer. He said, only by investing their lives could it be this way. He had lost too much, and yet he came again, this necessary repetition, like the tides.

He drew beasts with beasts, real beasts and fake beasts, immortal beasts and demon beasts, divine beasts and monster beasts. He painted a world where the divine beasts had become ordinary beasts, but you must not expect the divine beasts to be gone. They a re still there, with elongated bodies and eyes like lightning. He is a beast, you are a beast, one a divine beast, one a monster beast, and they all came to this time, to this moment. This moment is where divine beasts meet monster beasts, where real beast s confront fake beasts. Fake beasts seek to control the real beasts, but the real beasts cannot be controlled. They are as free as the wilderness, as bright as the moon. How could they be controlled by fake beasts? Fake beasts cannot recognize divine beasts, nor can they recognize themselves. They do not see them as animals, let alone as more ferocious animals than the divine beasts. Divine beasts live for sincerity, while ordinary beasts live for desire. One stroke captured the divine beasts living for sincerity, and also the beasts that looked like divine beasts but were not. He painted beasts with beasts, whether they were ordinary beasts or divine beasts, they all passed before our eyes. The withered grass and ba rren rocks of Songshan in winter were the backdrop of the painting, and the heart pounding in the chest of a fierce beast was like a Songshan moon. This heart is bright and clear, can you see it? Withered and wild, unrestrained, without routines, without constraints, all outdated customs and academic regulations were burned to ashes, leaving only the rare wild spirit, the appearance of a band of Liangshan heroes. Innocent and unpredictable, a long-unatte nded forest grew into rare and exotic trees. Civilization formed in the wilderness, not in classrooms.

He painted an unnamed supernatural world with no beginning or end, for he had to fiercely guard it. Guarding was not always gentle; gatekeepers were often fierce, and some Zen masters were too. Perhaps only extremely rare times of literary governance would guard with gentleness, but most eras required fierce protection of sincerity. Without sincerity, everyone was just animals. I once saw a Ming Dynasty portrait of Confucius that was both fierce and kind. I've heard of a Zen master who struck a disciple with a slap that broke three temporal lines. In the painting, the beasts were all fierce, guarding not a land of gentleness or mere rhetoric, but a heart that pierced through heaven and earth.

He drew the most enigmatic self-portrait and the most enigmatic group portrait of this era: beasts with beasts, spirits with flesh, you and me. He came again, a divine creature-deer from the Dunhuang murals, a fierce tiger-spirit fox from the Thousand Buddha Caves. Ruan Ji wept in despair at a dead end, but he could not stop laughing wildly, leaping out from the darkest depths of our memories, from the vast sea of death we created, a monstrous creature never seen in our lives. This person was Yi.

He shattered his life and re-forged it. What he aimed to accomplish was the original mission of art—to paint as he pleased, to do as he willed, with no rules, no boundaries. Everywhere he looked, there was poetry; with a stroke of his hand, a painting was complete. It was not he who was painting, but that which was painting; it was not he who was laughing, but that which was laughing. A laugh that spanned a thousand years, a laugh that lasted a myriad of years. Art lost its true essence in some point of the last century and has never returned. Humans have lost the means to commune with all things. Entering the realm of life with a sense of self is vastly different from entering it without a sense of self. With a sincere heart, he entered the realm of life, a nd the divine beasts he painted seemed to be painting themselves. The semi-divine, semi-human figures he depicted appeared to be painting themselves.

He came from the world of spirit beasts to the world of animals, from the Shan Hai Jing world to the world of fierce animals. Although he looked fierce, he was actually a protector. The spirit beasts, auspicious beasts, and laughing beasts he depicted leaped out of the stagnant water, like a heavy punch landing in the heart of the living dead. The leap of those spirit beasts and the leap of those fierce beasts were like a first strike, a second strike, a third strike, awakening us who are bound, regulated, and controlled, stirring our souls with what we had never seen before. Our skulls were electrified, and in an instant, they were stripped of their wild, savage, ruthless, and absolute nature, cleansed by their killing power and their spiritual eyes.

Five days in Song Mountain, touring Shaolin, viewing the grottoes, seeing Shaoshan and Taishan as if seeing heroes, they suddenly become enigmatic, yet exude the chivalrous spirit of a sword drawn from its scabbard, reigning supreme in the heavens and eart h. Song Mountain is a great protector, a protector of the one flower blooming into five leaves, with layers of rugged peaks and valleys, blending hardness and softness, permeated with a true energy that never dissipates. This is a place to practice a heart as solid as a wall, where Huìkě amputated his arm, where the Two Chengs studied, and where the Zizhi Tongjian was penned. The entire Dengfeng is imbued with a protective atmosphere, as if it holds supreme treasures. What kind of character can be worthy of Shaoshan and Taishan? What can be worthy of the historical legacy here? For a hundred years, we have been too weak to be worthy of the 4,500-year-old cypress trees of Songyang Academy, or the Han Three Tombs, which guard sincerity, while we guard falsehood.

Like the Hercules in Gongyi Stone Cave Temple, emerging from the stones to guard this ancient task, Like the two Han Dynasty at the entrance of Middle Peak Temple, emerging from their simple and sincere nature to guard the same ancient task, nothing has been forg otten. This task is never forgotten for a moment, fighting for the truth and sincerity. How can one guard without truth and sincerity?

The land of Song Mountain is like a bowl of white porridge simmering in a sandpot, growing whiter with each passing moment, a place of genuine combat, a place for the true nature to see the light of day. We have been trapped in the cage of civilization, wh ile he has returned to nature. Art needs to offend, Yi Le’s art is an offense to the eyes accustomed to the classroom. Art needs to break the rules, Yi Le’s art proclaims that the seemingly correct art is dead. Art needs to record, Yi Le’s art preserves the scent of the era like a watchdog. Art needs the strongest voice, and Yi Le’s art is that voice.

December 6, 2024