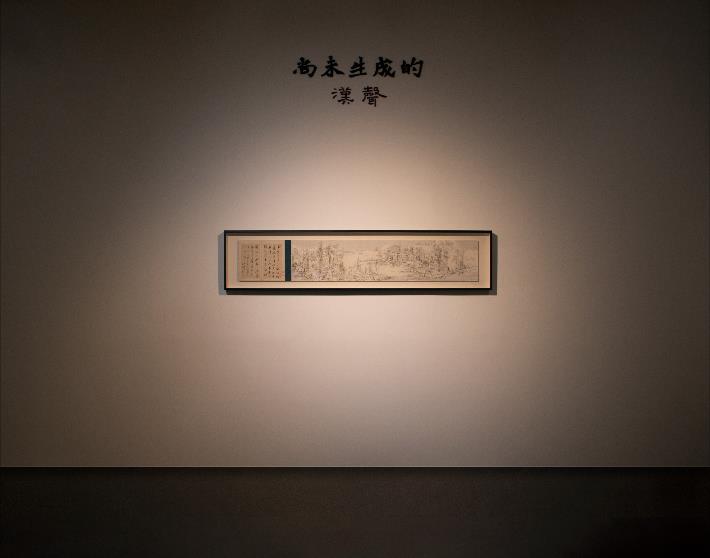

Why Rebuild Han Sheng?

By Yang Jian

For a century, our civilization has become a ruin, a fact that occurred when I was born. And as this civilization became a ruin, countless people would either become alienated or inhuman, with various misfortunes indeed stemming from the ruin of civilization. Such conditions have not improved until today. Here, I first speak of mourning, and in my place of mourning is where our reconstruction will take place. But today, what I mourn is not a specific person, but the current state of a civilization that has been ruined.

First and foremost, I mourn the loss of many details of life that we as Chinese people are experiencing, such as the opening lines of the "Zhu Zi Family Precepts" which say, "Rise at dawn to sweep and clean the courtyard," and "Every grain of rice and every mouthful of food, think of the effort it takes to come by, every thread and every strand, always remember the difficulty of producing goods." Whenever I see such phrases, I feel a sense of helplessness, a poignant nostalgia for this distant yet familiar voice of the Han people. For instance, our morning bowl of plain rice, you can only truly appreciate its happiness and usefulness after experiencing the materialistic tide from the 1980s through the 1990s and beyond. It is only after experiencing desire that we understand the value of simplicity, and only after weathering storms that we understand the clarity that comes with calm. A bowl of plain rice is a simple and clear way of life, and no matter where you are, a bowl of rice is enough. Simplicity is the fundamental path, and within it lies a clear mind. Once it disappears, it will inevitably be replaced by the path of desire. I remember in the 1970s, there was another detail in our lives: back then, there was virtually no trash. Excrement and urine were put to good use, and the cycle from start to finish was excellent. Often, one could see people collecting manure and carts pulling it. No chemical fertilizers were used; farmers were willing to work hard, and the mud they carried was used as fertilizer. Almost no plastic bags were seen, and everyone carried baskets, standing on the ground with a heart full of gratitude and care. Especially during autumn when the rice was golden, the gratitude for the earth's bounty was evident, making one's heart soft. In the past, all the details of life, from birth to death, followed the natural course. Now, this is no longer the case, and the reassuring details are becoming fewer and farther between. This shows that the true details of everyday life for a Chinese person have become ruins, and people have been reduced to mere animals for eating, drinking, defecating, and urinating, with the most vital details of life becoming increasingly hard to find.

The second point I mourn is that when people are reduced to mere animal existence, I remember that many of the characters I learned as a child were taught to me while I was held in my. parents' arms, during crowded gatherings where they rea d large posters and taught me the characters on them. It wasn't until later that I realized these posters were criticizing someone, meaning that my first exposure to written language was already tinged with hatred. In the 1990s, with the economic tide, our thinking and language became driven by greed. Subsequently, language continued to be simplified, instrumentalized, standardized, and technologized. In my education, the true form of language was rarely seen. Our Chinese language, when we first encountered it, was already not in its original form.

The third point I mourn is the ruins of the study of sages and virtuous people. The purpose and goal of ancient education were very clear: the lowest standard was to become a person, then a gentleman, then a virtuous person, and the highest standard was to become a sage. However, in our current education, it is already difficult to achieve the basic standard of becoming a person, let alone the highest standard of a sage. The biggest difference is that modern education teaches you to fall asleep, while the study of sages and virtuous people teaches you to wake up. One teaches you to sleep even deeper, while the other hopes for you to wake up completely. One is the complete loss of your original self, and the other is the complete restoration of your original self. This is the highest significance of Han Sheng. If you do not learn the teachings of seeing your true nature and establishing your essence as a virtuous person, even obtaining a doctoral degree would only mean existing as an animal that eats, drinks, defecates, and urinates. This refers to social education. In terms of family education, due to almost zero involvement in family education by several generations of parents, it has resulted in several generations of children.

Lacking personality and even the ability to live, this is what I mourn, as it is the disaster brought about by the collapse of sages' teachings. The fundamental purpose of sages' teachings is to help us discover our true self and establish it, solving all problems in the process. Modern education, on the other hand, helps people build a self that is overly utilitarian and arrogant. The most important thing now is the return of sages' teachings. Awakening and discovering the true self is the most crucial, which is the core of Han Sheng.

The fourth point I mourn is the ruins of filial piety. This is the most basic Chinese voice. In ancient times, governing the world with filial piety was a general principle. More than twenty years ago, on a late night, my uncle from the countryside suddenly appeared at my home, saying he had wanted to jump into the Yangtze River because his daughter-in-law was too harsh, and his son could not make a decision. Such situations were common in the countryside. There was also a story where my mother was critically ill, and her son returned to his hometown. Three days later, my mother was still suffering from her illness. The son said, "I only took seven days off, and you're still not dead. What should I do?" My mother died the next day. The son hastily buried her and went back to work. Formerly, every villager was a filial son, and when daughters married into other families, they only brought prosperity and never harm. What is the situation now? Both inside and outside the home, it is like this. Filial piety has become ruins, and this is so widespread and profound. If a filial son appears in a family, it is a matter of luck. In classical paintings, there was loyalty, loyalty to people, loyalty to mountains and rivers, loyalty to the heart, and loyalty to nature. Loyalty is the same as filial piety, which is the Chinese voice. Is there still such loyalty now?

The fifth point I mourn is the ruins of cause and effect. Master Yin Guang, a high monk from the Republic of China era, was asked how to govern the country. Master Yin Guang only replied with two words: cause and effect. Today, who still believes in cause and effect? In the past, even those who were illiterate believed in cause and effect. A single word, an action, or a thought all had their cause and effect. Now, even postgraduates and PhDs do not believe in cause and effect. Cause and effect have become ruins for many years. If there is no cause and effect, what can one not do? Without a view of cause and effect, self-discipline cannot be established, and where can life find its way to light? Governing the world with cause and effect does not require a single gun or bullet, which is why we were still a country without police until the Republic of China era.

The sixth point of mourning is the ruins of ritual. Ritual means respecting people. At its core, ritual embodies sincerity and respect, sincerity being self-sincerity, and respect being the relationship with others. Both point directly to the shared realm of life, and ritual is the path to this shared realm, not something as simplistic and crude as mere equality. Rather, it is the deepest and broadest shared realm among people, the realm of light. But once ritual becomes ruins, the inherent light of life will be obscured, and the heart will be in the long night without self-awareness. Music follows ritual; without ritual, how can there be the highest joy in human life? Ritual is the deepest and most essential form of equality. Ritual is the cause, and music is the effect; without ritual, there can be no music. Only through ritual, sincerity, and respect can we reach the shared realm of life; no other method will suffice. The Han voice is touching because it reaches the realm of sincerity and respect, and the same is true for classical paintings.

The seventh point of mourning is that ancestral worship has become a ruin. How many years ago I went to the countryside in Wan Nan, and how many beautiful and spacious ancestral halls have fallen into disuse. Those grand ancestral halls were built with the finest wood, the best stone, and the best craftsmen, showing how much our ancestors valued the respect for the deceased and the continuity of virtue. Without the concept of ancestors and forebears, it is hard to live in history and the greater life, and it is hard to have the depth and dignity of life. Moreover, your life would be hard to correct. Without ancestral worship, we lose our sense of life both vertically and horizontally. Now, why are people so self-centered and indifferent to gratitude? Could it be because of the absence of ancestral worship? Ancestral worship includes both preservation and renewal. Repeatedly painting landscapes is a form of ancestral worship of the landscapes.

The eighth point of mourning is the ruin of the concept of the mean. Harmony and balance, with the heavens in their proper place and all things thriving. For a hundred years, it has been overwhelmed by the supremacy of science and technology. What guides life is no longer the mean, but science and technology. How can there be nurturing and growth without the mean?

The ninth point of mourning is the submergence of the Pure Heart, the supreme treasure of the Han civilization. The Han civilization itself is a self-reflective civilization. Cold Mountain monk said, "My heart is like an autumn moon, a clear and bright jade p." ool. Nothing can compare to it, how can I describe it? " Master Huiyī said, "Spring blossoms fill the branches, the moon is full in the heart of heaven." Wang Yangming said before his death, "This heart is bright." The three people are conveying the same meaning: this heart like the moon is the supreme treasur e of the Han civilization. Do we still have it? What needs to be restored is our heart, not anything else. The problem lies right here.

The last thing I mourn is the ruins of the Way. "He who hears the Way in the morning may die in the evening content." Who can say this today? "Content with poverty and practicing the Way," who can say this today? "The exalted must fall, the living must die," this is what the Buddha's former life learned by offering his head, eyes, and brain. Chinese people talk about the Way, while foreigners talk about philosophy. The Way is something to practice, whereas philosophy is just for talk. "Embrace the One as the model for all under heaven," this is something learned through practice. We have gone from being the most talkative about the Way to the least, and the ruins of civilization are actually the ruins of the Way.

It is hard to imagine how civilization would take such a form. Until scholars like Qian Mu, Chen Yinke, Mou Zongsan, and Tang Junyi, among others, could all be considered sons of civilization. Our generation finds it hard to be called sons of civilization; instead, we are sons of greed, hatred, envy, and pride—never sons of civilization. We are a kind of animal existence outside of this civilization, still in our adolescence since the 20th century. This youth is characterized by betraying our parents, our a ncestors, and the sages and their civilization. For over a hundred years, we have been outside the lineage of our forefathers, outside this sage civilization, a situation unprecedented in China's thousands of years of history. We return empty-handed from t his treasure mountain, with countless treasures left unused in the ruins of our civilization. Thus, everything starts anew. This is my lament, followed by reconstruction.

There is a detail: In 1958, my grandmother walked several dozen kilometers from her hometown to bring us two gifts—a dressing table and a large earthenware jar. The dressing table is from the Qing dynasty, painted with mineral pigments that remain vivid to this day, though it is now in pieces. Only the large earthenware jar remains in the courtyard, solid and substantial. Every winter, the jar is covered in dust, yet the water inside is astonishingly clear. Perhaps the work of reconstruction can begin with the clear water in this jar and the vibrant colors on my grandmother's dressing table. Although I never met her, I believe these two items represent her face. This is where true reconstruction must begin, is it not?

Above, we discussed issues related to civilizational environments, which are not the main focus of this text. The following discussion addresses the reconstruction of Han Sheng in this environment. As is well known, for a century, we have been learning from others and have thus forgotten ourselves. What is discussed below might just be what we have forgotten, perhaps not limited to ten points, but more, but for now, let's discuss these points.

Firstly, Han Sheng embodies the beauty of non-desire. For instance, the Song Dynasty attendants in the Jin Temple of Shanxi, despite being lower-ranking, exhibit the beauty of non-desire. They may appear ordinary, yet they are unforgettable at first glance, due to their non-desire which gives them a sense of vitality. Suzhou gardens, composed of stones, water, wood, and plants, are completely devoid of desire, achieving a natural state that transcends human desires. Therefore, Han Sheng embodies non-desire. The heart finds peace in nature, not in desires, which is what Han Sheng represents. Non-desire leads to a pure appearance, a natural purity that touches and aligns the heart. A painting, a stone, a piece of calligraphy, after experiencing countless years, loses its fiery essence and reveals the beauty of non-desire. Thus, Han Sheng, whether in landscapes or in depictions of people, points to the beauty of non-desire, which can be so clear as to transcend the mundane.

Next, Han Sheng's ultimate goal is freedom and a vibrant life. To achieve this, one must let go of all attachments, big or small, making Han Sheng appear solitary and fresh. There is freshness in the solitude, and vibrancy in the freshness. The clarity of the pure nature emerges suddenly, bringing eternal freshness and vibrancy to true life. Only by freeing oneself from attachments can true life have the possibility of dawn, true life...

The light of life must shine for nothing exists without self, and humanity and divinity are one. Han Sheng seeks liberation rather than sinking into sensory pleasures. Day and night, Han Sheng ponders the transcendent, seeing something new every day without any repetition, grasping the essence of freshness and mystery. Jin Nong said, "The whole body is cool and clear," which describes the realm after liberation and freedom. Freshness is immediately apparent but profoundly deep. Following freshness is vitality.

Thirdly, is it one or two? Of course, we are one, but this one cannot be seen with the eyes or heard with the ears; it is true skill, only attainable through the shedding of roots and dust. One is merit and virtue, arising from purity, While two is defilement, arising from annoyance. One I s joy, while two is boundless suffering. One is supreme splendor, while two is endless attachment. The door of one opens inward, while the door of two is visible to the naked eye, leading to boundless suffering.

Fourthly, the magic of Han Sheng lies in transformation. A person, a drop of ink, a tear drop, all dissolve in the vast expanse of the universe. A frog's croak stands out particularly fresh in the realm of transformation, yet the frog's croak does not transcend this realm. The realm of transformation is the true realm, embodying complete equality. It was easier for ancients to return to this realm of transformation, but it is difficult for modern people to do so. The realm of transformation is seamless, like a perfectly uncracked egg, or like the streams that permeated the old county towns, each a pore-like waterway.

Fifth, the fundamental sound, Han Sheng, is rooted here, embedded here, and dwelling here. This is the root, so Han Sheng does not indulge in idle talk but enters and obtains from the root. Han Sheng discerns time by the rooster's crow in stillness, nurtur Ing life in the chaos.. Without clocks or the concept of time in knowledge, Han Sheng aligns with the virtue of heaven and earth, the brightness of the sun and moon, and the order of the four seasons. Han Sheng lives in the time of heaven, earth, sun, an d moon, not in the time of a clock. Han Sheng is nurtured by the time of heaven, earth, sun, and moon, whereas anxious clocks cannot produce Han Sheng.

Sixth, immobility is Hansheng. Returning to the root is said to be calm, and calmness is said to be returning to one's true nature. The more calm you are, the closer you are to the truth of life. The truth of life is neither birth nor death. The more calm you are, the closer you are to the immortality inherent in your life. When desires diminish to near nothing, you return to your original self. There is an inherent immobility in your original self, so when we view Chinese classical landscape paintings or figure paintings, there is always a profound immobility in both the front and the back, like a great mountain standing firm in the picture. Even a small painting has this immobility. This immobility is the immortality inherent in our life. Therefore, Han Sheng art begins by grounding itself in the true nature of life. When art returns to its true nature, the details it presents on the canvas are profoundly moving. Chinese landscape paintings or figure paintings always have a life's true nature that is neither born nor dies, which moves the heart. Therefore, life itself is clear and bright, and his paintings naturally are as well.

Seventh, the non-self is at the core of Han Sheng's teachings, as letting go allows the inner life's bow to quietly draw back. The more one lets go, the tighter the bow is drawn, until finally, true power fills the picture. Letting go is like forging a sword, always ready to plunge the body into the flames and merge with the sword. Thus, there is almost no bodily presence, only spirit remains, much like a Zen master's verse, where each word you recognize but the meaning eludes you. There are no people in the mountains, yet the trees grow in a never-seen-before blend of strangeness and freedom. There are no people in the mountains, yet the flowers bloom in a never-seen-before beauty and fragrance. The ancients created a wondrous realm of having and not having people. Another benefit of letting go is that his paintings gain a gentle power. Only a mother can bring us back to the Chinese language and to its elasticity. The few gentle threads of Chinese language are subtly reinforced by a father's strength behind them.

Eight, this refinement is from Hansheng. I have met refined individuals; some people are naturally refined from birth. Nowadays, it's hard to find refined people, to the point where even male students are difficult to recruit in Chinese literature departments. Where does refinement come from? It can only come from the heavens now. The faces of Chinese scholars are refined, and the faces in Chinese paintings are also refined. Refinement is nurtured by sages and civilization and the spirit of heaven and earth. What do we use to nurture it now?

Ninth, how to benefit others through Han Sheng. Han Sheng is actually hard to understand and very abstract, due to its transcendent nature, which is the art of seeing through everything, rather than the art of youth, But more of a senior art. Even a lady (la Dies' picture) or a erotic picture, transcendence is present within them. The less I have of transcendence, the more sacredness follows; the less two parts I have, the more sacredness follows; without it, true benefit to others will appear. The main characteristic of Han Sheng is its transcendence, which leads to benefit to others. The transcendent nature of Han Sheng has persisted until the Republic of China when it began to decline. Without transcendence, I become the master, thus completely reversi ng and breaking away from Han Sheng. The thousands of years of selflessness rooted in the way of non-self and the way of nature are now anchored in the easily decaying self. Only true selflessness can allow a mirror to appear, and a painting to eternally b enefit others. If Han Sheng cannot benefit others, it cannot continue in time.

Tenthly, everything is like a dream to Han Sheng, as a poem by Qiu Chuzhi describes this dream:

Yesterday, flowers bloomed in full red,

Today, flowers have fallen, leaving myriad branches empty.

Prosperity truly relies on the beauty of three spring months,

Changes are vain, following a night's wind.

Time outside the world is inherently self-enjoyed,

Life and death among humans, who can exhaust them?

A hundred years of great and small, flourishing and withering events,

Pass before one's eyes like a dream.

Hope lies in awakening, in emptiness, in the absence of self. Essentially, it is in everything being like a dream; without this, there is no possibility of renewal and rebirth. There are so few discerning individuals, principled individuals, and those who act, individuals who undergo a transformation, in this world. For a hundred years, we have been learning from others and forgetting our own treasures, thinking that the wrong path is the right one. The world is in shambles, filled with Han voice, but no one listens, and no one wants it.

This century is too outward, too tense, too restless. We no longer have the ability to appreciate the calm and inward art of ancient people. Few people are painting in ink and wash anymore; no one is playing with this ancient and backward black anymore. No one is thinking about maintaining and innovating; everyone is following the fast lane.

Here recorded are but a few drops of Han Sheng's experiences, which interconnect and permeate each other, differing in name but not in meaning. Western discoveries reflect Eastern wisdom, and Eastern insights illuminate Western understanding; the East contains the West, and the West contains the East, with no clear distinction between East and West, high and low, or self and other.

When Shen Congwen returned to his hometown at eighty, he heard the Nuo opera and shed tears, exclaiming loudly, "This is Chusheng, this is Chusheng." Han Sheng is like millet, small in grain but most vital, capable of fostering life and growth.

May 31, 2024

List of Artists (sorted by age)

Liang Quan

Born in 1948 in Shanghai, his ancestral home is in Zhongshan, Guangdong. One of the most representative artists of Chinese abstract painting, he graduated from the affiliated middle school of Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts and later studied in the United St ates. He taught at the Printmaking Department of Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now China Academy of Art) and currently works and lives in Shenzhen. Liang Quan is one of the earliest artists in China to combine traditional ink and wash with abstract expres sion, creating a personal expression that connects Eastern and Western aesthetic languages yet remains distinct. Known for his representative ink and wash collages, his works unfold a serene and distant Zen sentiment. He has participated in major internati onal exhibitions such as "Great Heavenly Abstract—Chinese Art in the 21st Century" organized by the National Art Museum Curator of of China with the, Achille Bonito Oliva, the Sydney Biennale, and others. His works have been exhibited in solo shows at institutions s uch as the University of San Diego, the Bauhaus Archive Museum in Germany, and the Art House in Nuremberg. His works are also held in the collections of renowned art institutions including the National Art Museum of China, Shanghai Art Museum, Guangdong Mu seum of Art, Zhejiang Museum of Art, Hong Kong Art Museum, Hong Kong M+, British Museum, and the University of San Francisco.

Li Xiuchen

Born in Qingdao, Shandong Province in 1953. Graduated from Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now China Academy of Fine Arts) in 1982 with a bachelor's degree; studied at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, in 1988; graduated from the Scul pture Department of the Manchester Metropolitan University, UK, in 1990, obtaining a master's degree. Currently a professor and doctoral supervisor in the Sculpture Department at China Academy of Fine Arts, a researcher at the Sculpture Institute of the Ch ina Academy of Art, a member of the Sculpture Art Committee of the China Artists Association, and a vice-chairman of the China Sculptors Association. Lives and works in Hangzhou. Li Xiuchen was one of the early sculptors in China's sculpture scene to condu ct experiments with metal welding in the 1980s, and the first to construct sculptures through touch. As an important artist in China's contemporary sculpture scene, his artistic career spans over 40 years, actively participating in the forefront of sculptu re since the 1980s. His major public collections include: Washington State University, USA; Holes International Sculpture Park, Czech Republic; International Sculpture Park, Shijingshan, Beijing; International Sculpture Park, Yuzi Garden, Guilin; Jinbaosha n Art Gallery, Taiwan; Shanghai International Sculpture Park; Library of Zhejiang University; Zhejiang University of Water Resources and Electric Power; Long White Shan Yanji International Sculpture Park.

Yan Shanchun

Born in 1957 in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, he holds a bachelor's degree in Printmaking from China Academy of Art and a doctoral degree in Art History and Theory from the same institution. He served as a researcher and deputy director at Shenzhen Academy of Fine Arts. His painting style is gentle and clear, with profound implications. His works are collected and exhibited by institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the United States, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the China Academy of Art Museum.

Wang Tiande

Born in Shanghai in 1960. Graduated from the Painting Department of Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now China Academy of Art) in 1988, and later obtained a doctoral degree in Calligraphy from the same institution. He is currently a professor at Fudan Univer sity. Wang Tiande is renowned both at home and abroad for his revolutionary innovations in traditional Chinese art, and is considered one of the most important artists in the development of contemporary Chinese ink painting. Wang Tiande has developed a uni Que artistic language through his innovative technique of superimposed ink landscape with smoke-burned or incense-burned paintings. He has also integrated his landscape creations with ancient stele rubbings from his collection, seeking connections and dialogues between the anc ient and the modern, destruction and creation, the eternal and the fleeting. Wang Tiande has held solo and group exhibitions in renowned galleries and important museums and academic institutions both domestically and internationally, including the Metropol itan Museum of Art in New York, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Kansas Spencer Museum (2009), Sydney University of the Arts in Australia (2010), Suzhou Museum (2014), Today Art Museum in Beijing (2014), the Forbidden City Branch of the Palace Museum in B eijing (2015), the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco (2016), Guangdong Museum of Art (2017), and the National Art Museum of China in Beijing (2018). His works are also collected by international renowned museums and academic institutions such as the Britis h Museum, Oxford University Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Brooklyn Museum, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Art Institute of Chicago, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Royal Ontario Museum in Canada, and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Musée Cernuschi, Paris; Vancouver Art Gallery; National Art Museum of China; Today's Museum, Beijing; Shanghai Art Museum; Guangdong Museum of Art; Hong Kong Art Museum; Suzhou Museum; Nanjing University of the Arts Museum; Sichuan Fine Arts Institute Museum; Museum of Art, Bowdoin College, USA; Wu Zhen Museum, etc.

Nan Xi

Born in Yongkang, Zhejiang, China in 1960, Nan Xi graduated from the Chinese Painting Department of the Academy of Military Arts in 1986. He currently resides in Nan Xi Art Studio in Nanjingang, Beijing, and Nan Xi Art Studio in Shanghai, working as a free lance artist. Nan Xi successfully created three methods in ink and wash art: "Nan Xi Dotted Technique," "Nan Xi Brush Path," and "Nan Xi Three-Dimensional Ink and Wash," which became distinct features of his art. In 2013, Nan Xi was selected as one of the top ten most influential new ink and wash artists by a panel of ten renowned contemporary art critics, including Lu Hong, at the New Dimension Critics Nomination held at the China National Art Museum in Beijing. He participated in the nomination exhibition , receiving high recognition from the academic community. In 2018, at the "Summit and Glory · International Olympic Committee Beijing Winter Olympics Launch Ceremony" held at the Shanghai Tower, the Sammler Foundation awarded Nan Xi the "Outstanding Contri bution Award in Culture and Art." Nan Xi has held solo exhibitions at the Shanghai Art Museum, China National Art Museum in Beijing, Royal Academy of Arts Museum in London, Yu Xin Art Museum in Singapore, Art Basel Hong Kong's Hauser & Wirth Gallery, Hong Kong Hauser & Wirth Gallery, Hong Kong Arts Centre, Gui Dian Art Space in Beijing, Ren Ke Art Space in Hangzhou, and many other venues. He has participated in many important academic exhibitions and published numerous solo art collections. He is a pioneeri ng artist in the contemporary ink and wash field.

Sang Huoyao

Born in Zhejiang in 1963, Sang graduated from the Chinese Painting Department of the China Academy of Art and received a master's degree. Member of the Artistic Creation Guidance Committee of the Chinese Academy of Art, Deputy Director of the Institute of Chinese Painting of the Chinese Academy of Art, National First-Class Artist, Councilor of the China Artists Association, Research Fellow at the Wu Guanzhong Art Research Center of Tsinghua University. Currently lives and works in Beijing. Sang Huyao has co nsistently pursued the contemporary relevance of Chinese ink art and the internationalization of ink art. Starting from his own creative practice, he integrates Eastern philosophy and aesthetics with his unique insights into the present, continuously pursu ing spiritual aspirations beyond the physical form, Gradually forming a method of stacking square blocks and the concept of imagist art, which has become his unique artistic language and symbol. His works are primarily held in public collections such as the Nat ional Art Museum of China (Beijing), Today Art Museum (Beijing), Long Museum (Shanghai), Singapore Art Museum (Singapore), Huawei Art Foundation (Shenzhen), Shanghai Art Museum (Shanghai), Guangdong Museum of Art (Guangzhou), Shandong Museum of Art (Jinan) , Zhejiang Museum of Art (Hangzhou), and Ningbo Museum of Art (Ningbo). They are also permanently collected and displayed at the main venue of the G20 Hangzhou Summit in China, the main venue of the Shanghai Import Commodities Expo, and the Shanghai World Art Gallery.

Wu Yi

Born in Changchun, Jilin Province in 1966, with ancestral roots in Ninghe, Tianjin. Graduated from the Chinese Painting Department of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1993, studying under Professor Lu Chen and earning a master's degree, subsequently remainin g at the academy to teach. Currently, he is a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and the director of the fourth studio in the Murals Department. He works and lives in Beijing.

Since 1994, his works have been exhibited at important museums and art institutions both domestically and internationally, including the China National Art Museum, Pace Beijing, Song Art Museum, Hong Kong Art Museum, German National Gallery, Dresden State Art Collections, Hamburg Museum, Göttingen Museum, Louvre in Paris, Saatchi Gallery in London, National Gallery of Singapore, Asia Art Museum in Fukuoka, Japan, Tokyo University of the Arts, Torrance Art Museum in the United States, National Gallery of Mal aysia, and the Contemporary Art Museum in Zagreb, Croatia.

Wei Qingji

Born in Qingdao, Shandong in 1971, he graduated from the Chinese Painting Department of the Oriental Art Institute at Nankai University in 1995, earning a bachelor's degree. He completed his studies in the Graduate Class of the Murals Department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2003. In 2008, he graduated from the School of Art and Design at Wuhan University of Technology, earning a master's degree. Currently, he teaches at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. Wei Qingji's contemporary ink art not only showcases the painter's understanding of the characteristics of ink materials but also reflects his innovative approach to traditional techniques.

A profound and deep understanding, and skillfully conveying personal experiences and social cognition. The postmodern artistic style and the spiritual essence of traditional Chinese painting are closely linked to the boundless freedom of visual and imaginative space, which has enabled his works to gain widespread cross-cultural dissemination and resonance. His works have been invited to participate in over two hundred art exhibitions in more than twenty countries and regions, including the China National Art Museum, the National Gallery of Berlin, the Meridian International Center in the United States, the National Gallery of the Czech Republic, the State Tretyakov Gallery in Russia, the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico, the National Gallery of Malaysia, the Seoul Museum of Art in South Korea, the Palace Museum in Warsaw, Poland, the Asia Art Museum in Fukuoka, Japan, the National University of Singapore Art Museum, the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, the Hong Kong Art Museum, the Shanghai Art Museum, and the Guangdong Museum of Art, among others. More than thirty of his works are now collected by various art museums and public art institutions both at home and abroad.

Tian Wei

Born in 1973, Tian Wei graduated from the Chinese Painting Department of the Fine Arts Institute at Capital Normal University. He then studied Chinese painting under Professor Jia Yufu of the Central Academy of Fine Arts and Professor Du Dakaio of the Acad emy of Arts and Design at Tsinghua University. He is a guest professor at the High Research Institute of Comprehensive Painting Language at the Central Academy of Fine Arts and a commissioned painter at the Institute of Chinese Painting Creation under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. He currently works and lives in Beijing.

Tian Wei’s creations originate from his early training in meticulous brushwork and his experience in copying ancient architecture. In the process of gradually forgetting the imagery, he distills the spatial and temporal sensibilities of Chinese ink paintin g into a modern language, establishing his unique artistic expression. Over more than three decades of artistic practice, Tian Wei has gone through a phase where line was the primary element in his paintings, and has now entered a new phase of integrating brushwork language with spiritual expression. He infuses elements of Chinese calligraphy aesthetics into contemporary minimalism and abstract painting, delving into the contemporary forms of expression and aesthetic connotations of Chinese ink painting. Th rough his paintings, Tian Wei has created works that embody the essence of calligraphy, Using the character "painting" instead of "writing". The opposition between image and background is nearly eliminated, and the subtle boundary between nothingne ss and existence makes the characters in his works sometimes clear and sometimes vague. The clearly meaningful characters in his paintings become “extremely inconspicuous,” bringing with them symbolic and metaphorical implications.